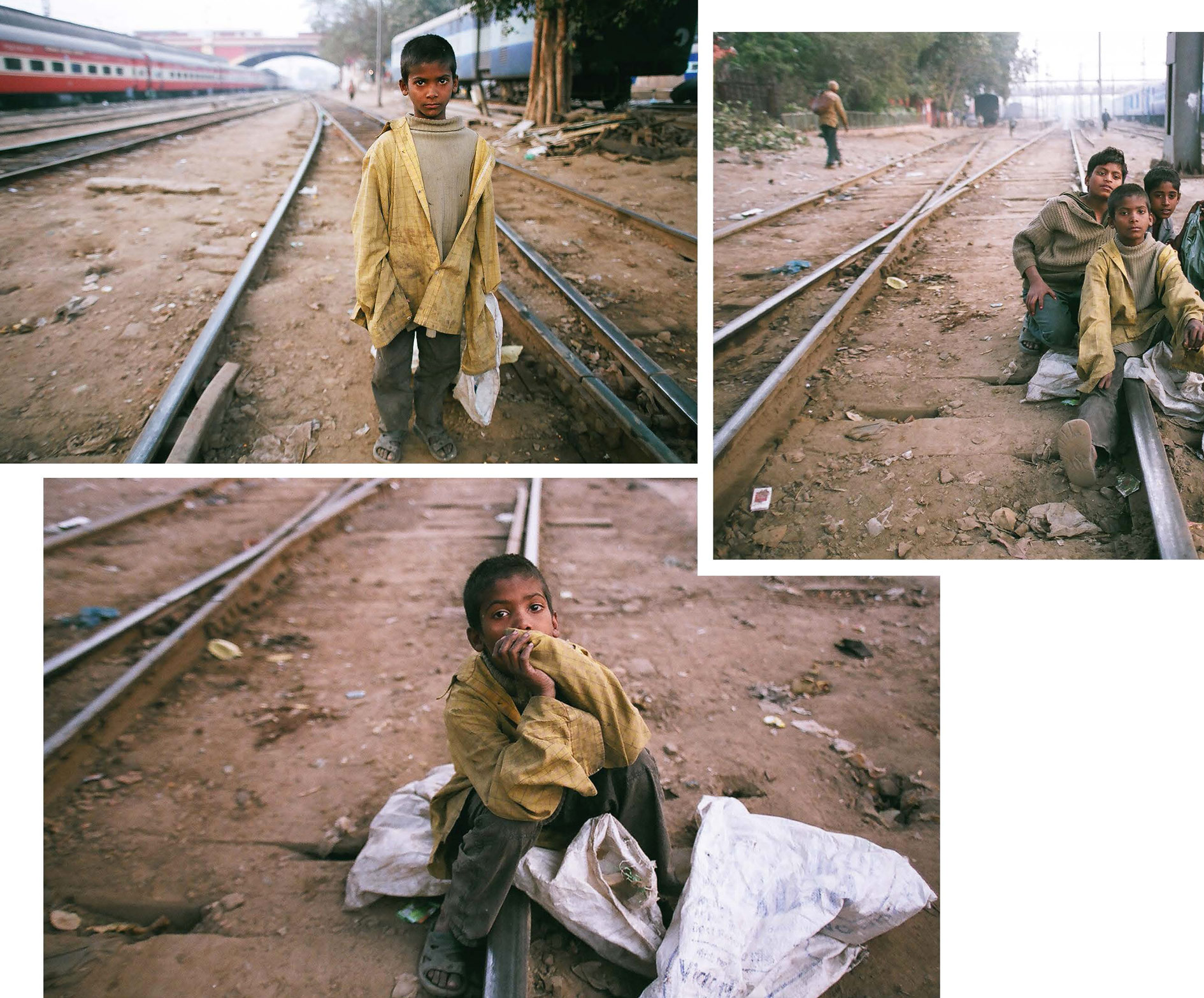

In India, over 12 million children live on the streets of sprawling cities such as Mumbai, Kolkata, Delhi and Bangalore. While some live with their families on the streets, many are alone. They must fend for themselves to survive, sleeping on railway platforms and footpaths or under flyovers and bridges. Worldwide, there are an estimated 100 million street children.

One of them is Jamile, who comes from Jharia, a town in the Indian state of Jharkhand. His father died when he was young, so, in order to help his struggling family, he found a job at a local food stall. The hours were long, with just one break during the whole day. After a few months, the stall owner suddenly decided to stop paying him. Feeling desperate, and responsible for supporting his mother and sister, Jamile stole 5,000 rupees (about $80) from the stall.

‘I was afraid. I didn’t know what to do... so I ran away. I didn’t want to leave home, but I thought I could make money in the city and bring it back,’ he explains.

A child arrives at a busy railway station in India every five minutes, often alone, bewildered, hungry and extremely vulnerable. Running away from abuse or poverty, they dream of adventure and a better life. But from the moment they step off the train they are surrounded by danger. When Jamile arrived at Sealdah Station in Kolkata, he was just eight years old.

There is never a still second at Sealdah station, never a moment of calm. Just constant noise and friction of people and cargo in motion. Every day, more than 120 trains come and go from the 15 platforms. It is among the busiest stations in Asia. Sealdah is a place where street children can scrape a living, selling refilled water bottles to commuters or begging from passers-by. But it is also a place of danger: a magnet for the pimps, drug pushers and so-called ‘beggar mafia’ who seek out lost children.

Running away from abuse or poverty, they dream of adventure and a better life. But from the moment they step off the train they are surrounded by danger

What happened to Jamile on arrival at Sealdah is ‘as tragic as it is commonplace’, says Navin Sellaraju, country director for India of Railway Children, a British charity which helps street children in India, east Africa, and back home in Britain. ‘Unable to return home for fear of retribution, Jamile remained at the station for almost three years. During that time, he was targeted by older boys who exploited him for financial gain and subjected him to appalling sexual abuse. One was a boy called Tapas, who mistreated Jamile in return for food and shelter at his home. Jamile drifted, almost inevitably, into taking drugs to numb the pain.’

Child-friendly stations

Railway Children has found and helped over 200,000 children like Jamile, but the charity has also become increasingly aware of the need to make train stations, in particular, safer places for children. The charity has responded by launching an initiative to create ‘child-friendly’ stations across India, working in partnership with a number of grassroots organizations that understand the local needs of their communities. This includes helping local police, station vendors and porters become more aware of the dangers the children face, and to stop seeing them simply as a nuisance.

Instead, when a child arrives at a ‘child-friendly’ station they are now offered help and referred to a ‘child protection booth’ on or near railway platforms, which are usually staffed by a volunteer or railway protection force officer. A separate but complementary initiative by the charity has been to provide former street children with first aid and hygiene training so that they can themselves become child health volunteers. Their role is to watch out for children arriving on train platforms who may be in need of medical attention. Newly arrived children are far more likely to trust their peers rather than authority figures, and to accept being referred by them to the local drop-in centre. This is where they are given food, clean clothes and medical care and can access longer-term help.

‘This approach ensures children get help as soon as possible after arriving at a train station, which is when they are usually terrified and most vulnerable to exploitation,’ says Navin Sellaraju. ‘Because Sealdah station was not part of our child-friendly programme when Jamile first ran away, help did not immediately reach him. But luckily he was eventually spotted by one of our rescue workers and taken to one of our centres.’ Jamile’s substance abuse had already begun to take its toll, Navin Sellaraju continues. He was ‘struggling to maintain any level of concentration’ and was emotionally volatile.

Urban jungle

But staying in one place proved too difficult for Jamile and he ran away again. Criss-crossing India’s vast and intricate railway network, he ended up at Ajmer Sharif, 1,600 kilometres from Kolkata. Once there, he tried to scrape out a meagre existence as a beggar. Fortunately, after a few months, he decided to return to the centre and, with the help of counselling, started to talk about the traumatic experiences that had defined the past three years of his life. He talked about the risks he had taken to survive on the streets, as well as the life at home he had felt forced to leave behind aged eight.

'All day I scavenged for plastic bottles and if I was lucky I made 100 rupees. Enough to buy some dahl and vegetables. We earn. We eat. That's it.'

‘It is like a jungle on the streets... very tough and very hard,’ Jamile says. ‘All day I scavenged for plastic bottles and if I was lucky I made 100 rupees [about $1.60]. Enough to buy some dahl and vegetables. We earn. We eat. That’s it.

‘There are other boys – older and bigger – who take drugs, beat up the smaller ones and steal our money. Then at night I am very tired, but going to sleep is hard. Someone might beat you up, take your money. The police do this a lot.’

After a few months at the centre, Jamile’s behaviour began to improve; he worked hard to get his drug addiction under control. Eventually, he agreed to let an outreach worker visit his family home with him and talk to his mother about what had happened after he ran away. But although she desperately wanted to look after her son, she said she was unable to, because of work commitments.

So, while Jamile remained at the centre, the charity instead arranged for his mother to make regular visits. As their relationship improved, he expressed a wish to live with his mother and further his studies.

Encouraged by the progress Jamile was making, his mother eventually decided she could take him back home. His outreach worker continues to stay in touch and is helping to get him enrolled in school.

‘Every day I missed my family. At the station and on the streets it is dangerous. Every day is a violent day. I want to go to school and learn so I never have to go back. I want to do something great one day,’ says Jamile.

‘If the right kind of help is offered to kids like Jamile the moment they arrive at Sealdah and India’s other big hub stations, we have a real chance of preventing them from being sucked into the criminal underworld. Once this happens, it is almost impossible to escape,’ explains Navin Sellaraju.

In a place like Sealdah station, where a child’s existence is determined by the narrowest of margins, the smallest changes can have a huge impact. Child protection committees have now been set up at Malda, Howrah, Itarsi, Asansol and Sealdah stations and have been tasked with finding ways to make them safer for children.

Meanwhile, Sealdah’s successful child protection booth service has led to new booths being provided at Patna, Howrah and New Jalpaiguri train stations, with more planned. Positioned right on the frontline, such initiatives offer children like Jamile a much better chance of avoiding the abuse, violence and poverty that continue to define the lives of so many of India’s street children. Instead, they are given – often for the first time – a chance to envision a very different and far safer future.

Terina Keene is Chief Executive of Railway Children.