‘You need to bring a parent to confirm what you are telling us,’ says the woman sitting behind a desk that dwarfs both her and the office it fills. ‘That is the only way we will be able to help you. Next!’ A woman walks out of the office, grumbling under her breath.

I empathize. I sometimes feel that Botswana customary law is standing still as time sprints past. Perhaps for some it is a romantic notion, one that I myself have retreated to when confronted with a too-fast present.

I believe there was a time, 50 years ago, when an instruction to fetch ‘a parent’ as a witness to satisfy a government requirement was feasible. All you needed to do was poke your head outside the window of your rondavel, greet politely and ask for a few minutes of your relative’s time. And in this traditional setting, parent meant any relative: your father’s sister, your mother’s brother, an aunt or uncle, an older cousin – anyone who could vouch for the fact that you were who you claimed to be. Back then, the village chief probably knew all their subjects by name. A chief could order the shutdown of the village – put all things on hold: no weddings, no ‘court’ cases, because when the first rains had fallen it was time for the able-bodied to go and till the land. And no-one would raise an eyebrow. Now I learn of the pronouncement of a village shutdown with some concern. Is it reasonable in this day and age?

The last year of writing this column has been one of re-learning about Botswana, about a new awareness of my home. Odd, that I have travelled the same road over and over again and then one day, as I look up, I am struck by things I had never noticed before. Gaborone City’s skyline has changed since the last time I really looked; billboards vie for the attention of passers-by. There are older ones that bear messages that have been overtaken by time: ‘Abstain, Be Faithful’, ‘Repent, For The End Of The World Is Nigh’. Soon there will be new ones bearing faces of those would wish to be voted into power in 2014. The aspiring leaders know it is time to start convincing us again because a year can race past. October has usually been the favoured month for general elections. Perhaps there is a reason. October is Phalane in the Setswana language. It is the time when impala foal and there is an adage that says that the wisdom of an impala springs from its young.

When votes are being garnered, we are urged to remember what it means to be a Motswana and we are told to hang on to traditions and do things the Botswana way – but what does this translate to?

On the local news channel, there is a gathering of government dignitaries. An entire village puts on its best show because one of their own is to be given a house. A ribbon stretches around the house like the yellow tape that is used to cordon off a murder scene. The recipient of the house weeps. It is obvious to all who are watching that her gratitude, like her tears, overflows. Immediately after, there is a TV debate with high-school children taking part. They demand to know what 47 years of independence have done for them.

And though I too am disillusioned sometimes, I will register to vote. Not for any chief, because in this democracy, chiefs are still born, not made. I will register to vote because somewhere deep down in my heart, I hope that my vote may make a difference even though I feel trapped between tradition and modernity. This has become much more apparent as I have had to examine the reality of Botswana.

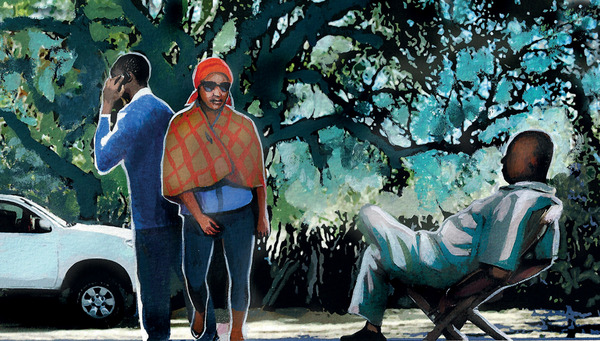

I am still thinking about the easiest way to find an adoptive parent when a couple roars past in a 4 by 4. As the driver gets out of the car, he pulls out his cellphone and stops to have a conversation. The woman he is with is wearing stilettos and sunglasses. She has covered her shoulders with a shawl. Her hair is tucked inside a wrapper. When he gets off the phone, they continue towards the chief, who is sitting on a bench under a large shady tree.

This is the incongruity of Botswana. Tradition and modernity, colliding, co-existing, blending.